I have always had this nagging question in the back of my mind. Why is it that sociology, a field utterly obsessed with the intricacies of human groups, spent so much time looking the other way when it came to one of our most brutal, yet defining, collective behaviors? I am talking about war. It feels like we were happy to dissect family dinners and classroom dynamics, but the messy, world-altering business of organized violence was politely handed over to the historians and political scientists. That always bothered me. How can we claim to understand society if we ignore the very forces that so often tear it apart and reshape it? Thankfully, that mindset has started to crumble. The sociology of war and peace, as a dedicated field, is actually a surprisingly recent invention. It only really began to find its footing in the late 1950s.

Picture this: a bunch of academics and peace activists, fueled by post-war anxiety and a new scientific zeal, decided to merge their passions. Pioneers like Johan Galtung, who started the Peace Research Institute Oslo, insisted we could not just wish for peace; we had to study it systematically. Can you imagine the pushback? The idea of “peace research” seemed too political, too soft for serious science. But they pushed on, and I find that incredibly inspiring. It is a powerful reminder that sometimes the most obvious topics are the ones we are most reluctant to touch. So, what does this field actually do? At its heart, the sociology of war is not about battle tactics or weaponry. It is about people. It asks how social forces make war possible and how the experience of warfare, in turn, completely transforms a society. Think about it.

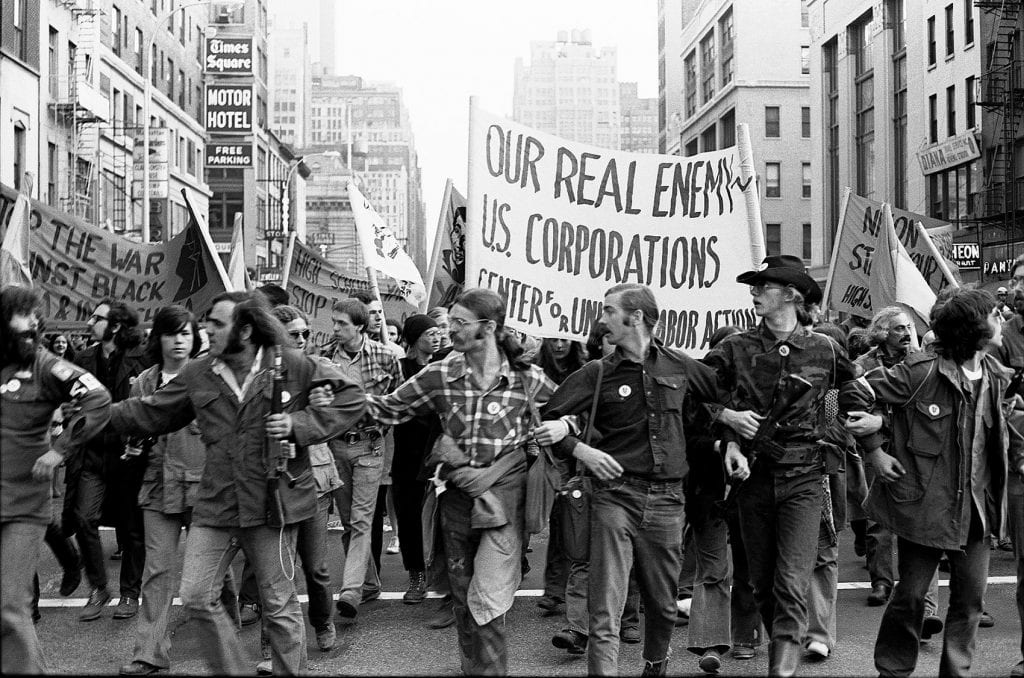

Why do some communities rally for a fight while others protest? How does being in the military change a person’s worldview? I remember my grandfather, who never spoke much about his service, but carried a certain quiet camaraderie with his old army friends his entire life. That is the social glue of war, a bond forged in extreme circumstances. This exploration into the sociology of war and peace aims to understand not just the politics of conflict, but the very fabric of human connection and disruption it creates. Wars are not just fought by governments; they are lived by entire societies, leaving deep, lasting scars on everything from our economy to our collective memory. But here is the real kicker. Studying peace has turned out to be even trickier than studying war. What do we actually mean by peace? Is it just the quiet after the guns stop? Scholars call that negative peace, and while it is better than the alternative, it feels a bit empty, don’t you think? The more compelling idea is positive peace. This is not just an absence of violence, but the presence of justice, equity, and what some call a moral sensibility.

This idea truly resonates with me. I think about places like Northern Ireland or Rwanda, where official peace agreements were signed, but the social landscape remains fractured. True peace is not just a document; it is a “social peace process. It is the slow, painful, grassroots work of rebuilding trust between neighbors who were recently enemies. It is the unglamorous work of healing. What fascinates me most about modern research is the realization that war and peace are not simple on/off switches. They are more like a dimmer switch, with societies existing in varying shades of conflict and cooperation all the time. The old rules do not always apply anymore. We see “new wars” fought by non-state groups, where the lines between soldier and civilian are intentionally blurred. These conflicts do not have neat beginnings or endings; they simmer, fueled by social media and ancient grievances alike.

A strong sociology of peace and conflict is crucial here, because it helps us see how these wars are embedded in the daily fabric of social life, often feeding on existing inequalities. On a practical level, researchers in this field have gotten really creative. They have built massive datasets, like the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, to track violence patterns across decades. This number-crunching is vital; it helps us move beyond gut feelings to see what actually correlates with the outbreak of war. But for me, the real understanding comes from the qualitative stories, the interviews with former child soldiers or the mothers leading reconciliation efforts. The data tells us the “what,” but the stories tell us the “why.” We need both to grasp the full, human picture. In the end, my journey into this topic has convinced me that sociology is not just an observer here; it is an essential voice. War is, at its core, a social phenomenon. Therefore, building a lasting peace requires a social transformation. We have to understand how propaganda works on a crowd, how military culture impacts a nation, and how to mend the torn social fabric of a post-conflict community. These are not side issues; they are central to the whole messy, heartbreaking, and hopeful project of humanity. The sociology of war and peace may have been a latecomer, but its insights feel more urgent than ever.

References

American Sociological Association. (n.d.). Peace, war, and social conflict. *ASA Sections*. Retrieved from https://www.asanet.org/asa_sections/peace/

Brewer, J. D. (2022). *An advanced introduction to the sociology of peace processes*. Queen’s University Belfast. https://www.qub.ac.uk/Research/GRI/mitchell-institute/ResearchandImpact/Blogs/250322JohnBrewer-PeaceProcesses.html

Gleditsch, N. P., Nordkvelle, J., & Strand, H. (2014). Peace research: Just the study of war? *Journal of Peace Research*, 51(2), 145-158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343313514074

.